The magic behind 💅 styled-components

November 30th, 2016

If you’ve never seen styled-components before, this is what a styled React component looks like:

const Button = styled.button`

background-color: papayawhip;

border-radius: 3px;

color: palevioletred;

`

This Button variable is now a React component you can render just like any other React component!

<Button>Hi Dad!</Button>

So, how the does this work? What kind of transpiler babel webpack magic thing do you need to make this work?

Tagged Template Literals

As it turns out, this weird styled.button`` notation is actually part of JavaScript, the language! It’s a new feature called a “Tagged Template Literal” introduced in ES6.

Essentially, it’s just calling a function – styled.button`` and styled.button() are almost the same thing! The differences become visible as soon as you pass in arguments though.

Let’s create a simple function to explore this:

const logArgs = (...args) => console.log(...args)

This is a pretty dumb function which does nothing except log all arguments passed into the function call.

You can follow along this explanation (in any modern browser) by pasting the above function and executing the following code samples in the console

A simple example of usage:

logArgs('a', 'b')

// -> a b

->denotes a log in the console for this post

Now, let’s try calling it as a tagged template literal:

logArgs``

// -> [""]

This logs an array with an empty string as the first and only element. Interesting! I wonder what happens when we pass a simple string in?

logArgs`I like pizza`

// -> ["I like pizza"]

Okay, so that first element of the array is actually just whatever is passed into the string. Why is it an array then?

Interpolations

Template literals can have interpolations, which look something like this: `I like ${favoriteFood}` Let’s call logArgs with parenthesis and a template literal as the first argument:

const favoriteFood = 'pizza'

logArgs(`I like ${favoriteFood}.`)

// -> I like pizza.

As you can see, JavaScript goes ahead and puts the interpolations value into the string it passes to the function. What happens when we do the same thing, but call logArgs as a tagged template literal?

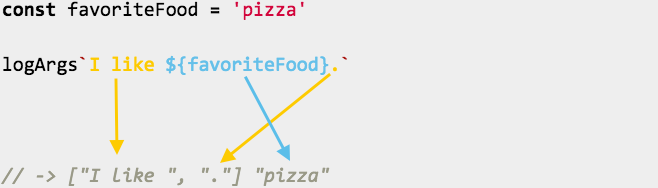

const favoriteFood = 'pizza'

logArgs`I like ${favoriteFood}.`

// -> ["I like ", "."] "pizza"

This is where it gets really interesting; as you can see we didn’t just get a single string saying "I like pizza". (like we did when we called it with parenthesis)

We still get an array as the first argument, which now has two elements: the I like part right before the interpolation as the first element and the . part after the interpolation as the second element. The interpolated content favoriteFood is passed as the second argument.

As you can see, the big difference is that by calling logArgs as a tagged template literal we get our template literal all split up, with the raw text first in an array and then the interpolation.

What happens when we have more than one interpolation, can you guess?

const favoriteFood = 'pizza'

const favoriteDrink = 'obi'

logArgs`I like ${favoriteFood} and ${favoriteDrink}.`

// -> ["I like ", " and ", "."] "pizza" "obi"

Every interpolation becomes the next argument the function is called with. You can have as many interpolations as you want and it will always continue like that!

Compare that with calling the function normally:

const favoriteFood = 'pizza'

const favoriteDrink = 'obi'

logArgs(`I like ${favoriteFood} and ${favoriteDrink}.`)

// -> I like pizza and obi.

We just get one big string, everything mushed together.

Why is this useful?

That’s nice and all, so we can now call functions with backticks and the arguments are slightly different, whahooo. What’s the big deal?

Well, as it turns out this enables some cool explorations. Let’s take a look at styled-components as an example of a use case.

With React components, you expect to be able to adjust their styling via their props. Imagine a <Button /> component for example that should look bigger when passed the primary prop like so: <Button primary />.

When you pass styled-components an interpolated function we pass you the props that are passed into the component, which you can use to adjust the components styling:

const Button = styled.button`

font-size: ${props => props.primary ? '2em' : '1em'};

`

This Button will now have a font size of 2em if it’s a primary button, and a font size of 1em if not.

// font-size: 2em;

<Button primary />

// font-size: 1em;

<Button />

Let’s go back to our logArgs function. Let’s try calling it with a template literal with an interpolated function, just like above styled.button except we don’t make it a tagged template literal. What do we get passed?

logArgs(`Test ${() => console.log('test')}`)

// -> Test () => console.log('test')

The function gets toString-ified and logArgs gets a single string again which looks like this: "Test () => console.log('test')". (note that this is just a string, not an actual function)

Compare this when called as a tagged template literal:

logArgs`Test ${() => console.log('test')}`

// -> ["Test", ""] () => console.log('test')

Now I know this isn’t obvious in the above text, but what we get passed here as the second argument is the actual function! (not just the function as a string) Try it in your console to see it better, and play around with it a bit to get a feel for this.

This means we now have access to the function and can actually execute it! To examine this further, let’s create a slightly different function that will execute every function it gets passed as an argument:

const execFuncArgs = (...args) => args.forEach(arg => {

if (typeof arg === 'function') {

arg()

}

})

This function, when called, will ignore any arguments that aren’t functions, but if it gets passed a function as an argument it will execute it:

execFuncArgs('a', 'b')

// -> undefined

execFuncArgs(() => { console.log('this is a function') })

// -> "this is a function"

execFuncArgs('a', () => { console.log('another one') })

// -> "another one"

Let’s try calling it with parenthesis and a template literal with an interpolated function again:

execFuncArgs(`Hi, ${() => { console.log('Executed!') }}`)

// -> undefined

Nothing happens, because execFuncArgs never even gets passed a function. All it gets is a string that says "Hi, () => { console.log('I got executed!') }".

Now let’s see what happens when we call this function as a tagged template literal:

execFuncArgs`Hi, ${() => { console.log('Executed!') }}`

// -> "Executed!"

Contrary to before, what execFuncArgs gets passed as the second argument here is the actual function, which it then goes ahead and executes.

styled-components under the hood does exactly this! At render time we pass the props into all interpolated functions to allow users to change the styling based on the props.

Tagged template literals enable the styled-components API, without them it could (literally!) not exist. I’m very excited to see what other use cases for tagged template literals people come up with!

Liked this post? Sign up for the weekly newsletter!

Be the first to know when a new article is posted and get an inside scoop on the most interesting news and the freshest links of the week. (I hate spam just as much as you do, so no spam, ever. Promise.)

Tweet this article